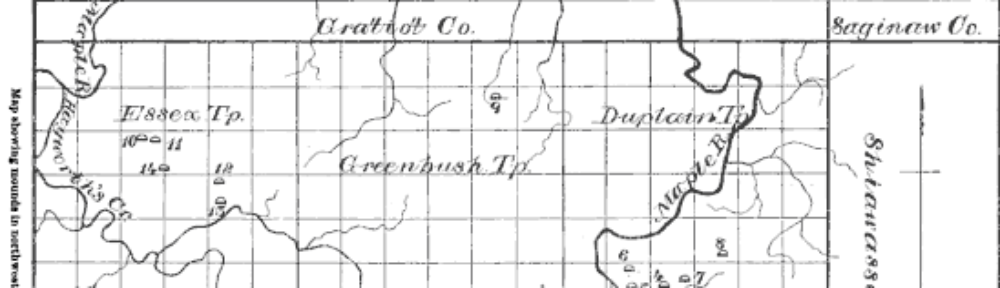

According to M.L. Leach’s Smithsonian Institution Annual Report titled, “Ancient Mounds in Clinton County, Michigan,” in 1885 over twenty mounds could still be discerned amid the rapidly changing landscape. My grandfather’s farm is near number 16 (bottom right). However, as Leach observes, by the end of the nineteenth century the mounds were rapidly disappearing due to farming implements as well as deliberate removal by inhabitants. Many of these bones were shipped to Glascow, Scotland for analysis. I doubt if they were ever returned.

We live in a colonial state. These mounds belonged to the people who lived here before me, people my ancestors drove from the land through violence and deception. My own great-great-grandmother, Lily Rail, signed the Saginaw Treaty of 1819, wherein most in which most of the Chippewa and Ottawa lands in mid-Michigan were ceded to the United States government. According to Charles Cleland, in Rites of Conquest: The History and Culture of Michigan’s Native Americans, the US gained 6 million acres of land, roughly one third of the Lower Peninsula from this treaty. Governor Cass prepared for the his meeting with the tribes by purchasing “39 gallons of brandy, 91 gallons of wine, 41 ½ gallons of fourth proof spirits, 10 gallons of whiskey, and 6 gallons of gin.” The tribal leaders were shocked by Cass’s proposal to buy their ancestral land. With the War of 1812 only five years behind them, they expected a proposal for peace. As Ogamawkeketo, a chief speaker said, “You do not know our wishes. Our people wonder what has brought you so far from your homes. Your young men have invited us to come and light the council fire. We are here to smoke the pipe of peace, not to sell our land.” And yet, Cass and his traders (most of whom were married to Native American women) and interpreters were willing to go to any length to secure these lands, including bribery and intoxicating tribal leaders. Most of the Chippewa and Ottawa who were forced from their homes were never compensated for the lands the government took from them, while white traders secured a tenth of the land and the majority of the cash paid for the land.

Once the government owned the area, they could sell it to entrepreneurs. The Michigan lumber industry was the most profitable enterprise in US history. Millions of acres were clear-cut, clogging the rivers as they were transported. Many species of fish, such as the grayling, went extinct. Soon the passenger pigeons would go extinct as well, a bird that was once so numerous, flocks were known to black out the sky.

What is this place where I grew up? Ovid, Michigan? A strange landscape, an alien landscape, a transformed landscape, a landscape in mourning, a ravaged landscape. I try to use art to reconnect to the these spaces, to help with my feelings of alienation, but the truth is, a part of me died with those ecosystems, a part of all of us died. There is no going back. And yet, we must go forward with the knowledge of what is lost. Where there is life, there is hope. There is hope.