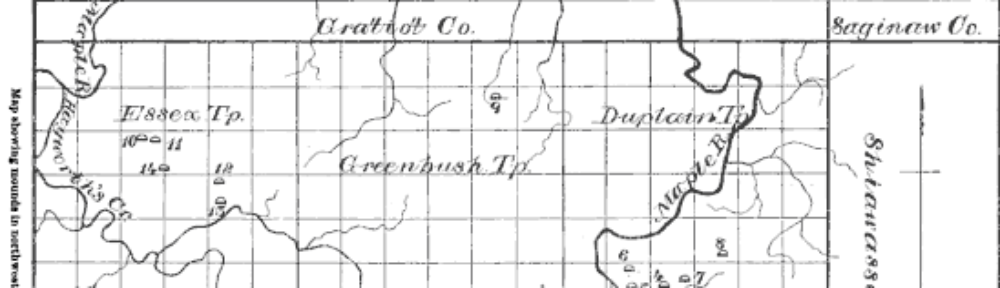

My new play in verse, Faun, can now be ordered from 53rd State Press! In Faun, I explore the sudden erasure of human and nonhuman populations from my hometown of Ovid, Michigan. Embodying various voices, forms, and media, a young girl named Lily undergoes a series of transformations, guided by nymphs, flora, and fauna. A reworking of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Faun also reflects on the themes of sexual violence that often occur in the mythic.

Praise for Faun:

Faun is a book like no other. Part feminist mythology, part play, part song, this enigmatic and shamanistic text pushes us intellectually, visually and sonically to navigate a world of wolves, bears, foxes, roots, robins, gnats and eyes. Each character, or set of characters, is given a voice to comment on permutations of Lily, the book’s incredible heroine. Faun begins with an act of sexual violence and demonstrates how that act ripples and reverberates through the “moss-multitudes,” much the way they do in a place like Ovid, Michigan. Steeped in the modernist tradition, George writes beautifully of those on the brink, who “can barely stay in the world,” yet survive in order to create new ones.

—Sandra Simonds, author of Orlando

Brandi George’s Faun is a magical reconstruction of a terrible past into an operatic collection of voices that sing together of the natural world imperiled. Ovid’s Metamorphoses is superimposed on Ovid, Michigan, and Lily sings through the generations in an aria that gives voice to trees, rivers, fire, roots, stone, ants. Lily travels to the Underworld. Lily becomes a nymph. Lily lives in the present and the deep primordial past. The upper world and the underground world are utterly mysterious and yet all the voices rise and tell a story of immeasurable tragedy and beauty. Faun is driven by its gorgeous language and by George’s powerful voice in a poetic tour de force.

—Barbara Hamby, author of Bird Odyssey

In this fake-book of flinches, I am translated to a post-lapsarian space along the shores of Lake Superior, to Ovid, Michigan, a space of prolapse, where fibrous teratogens pump like wasps in the vein. George’s Lily lapses in darkness; goes errant; all creatures voice around her; she imbibes the poison of Poesie; extricates painfully from herself the barb of settler-inheritance; converts Ovidian logic from to rape to consent; and thereby becomes the scene of her own crime-against-society—progenetrix of lyric monsters.

—Joyelle McSweeney, author of Toxicon and Arachne

Excerpts from the manuscript may be found at Columbia Journal; Fence; Forklift, Ohio; Gulf Coast, Hiram Poetry Review; Newfound; The Ocean State Review, Orion, and South Florida Poetry Journal.